VAPORWAVE MEGATEXT:

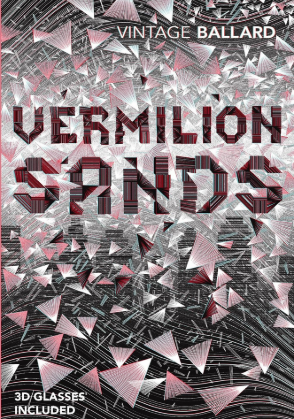

VERMILION SANDS By J.G. Ballard

Written By: Michael Uhall

Published on: Tuesday January 30th, 2024

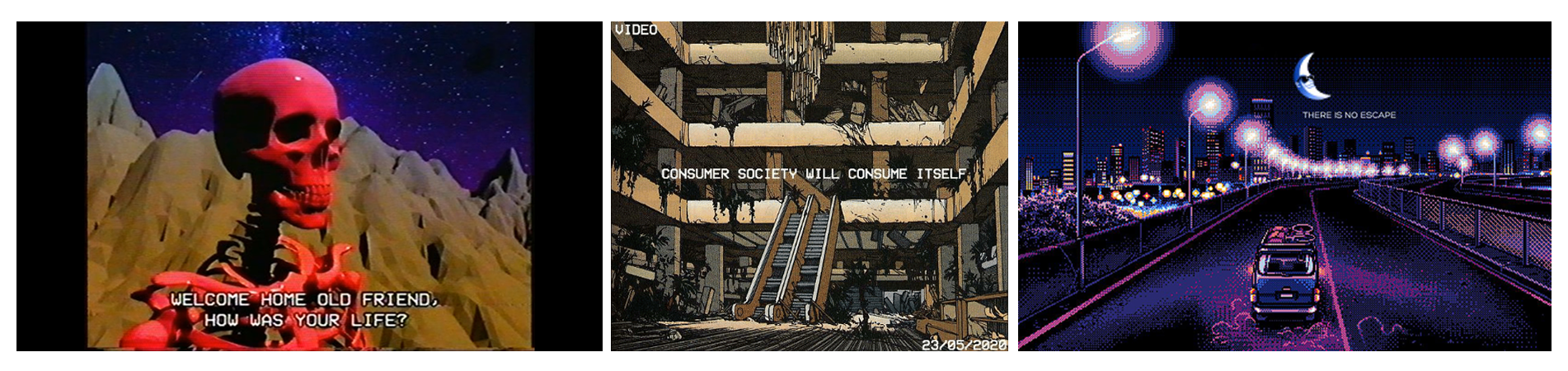

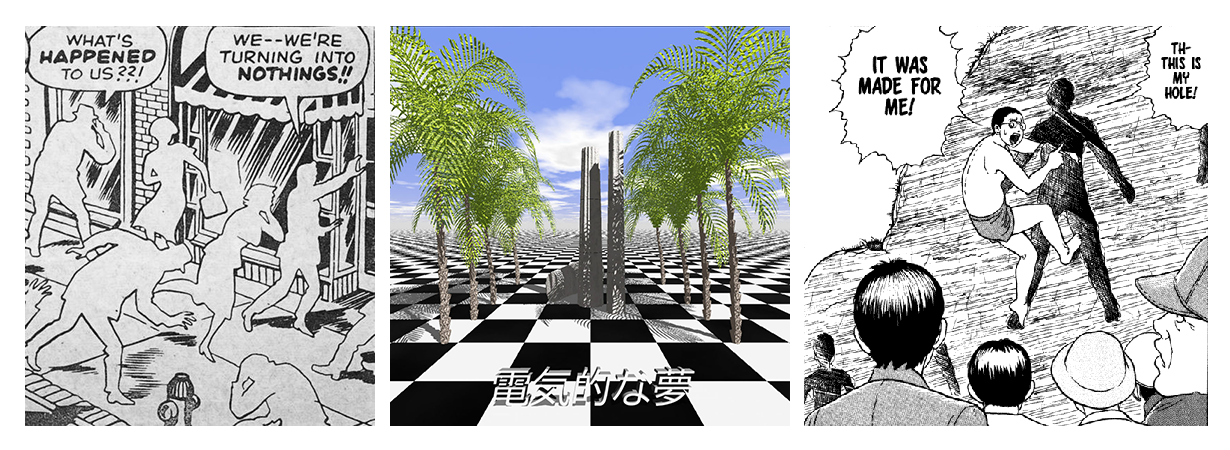

First released on June 15, 1987, the GIF (Graphical Interchange Format) was invented two years before the Cold War went underground, making it truly an artifact from before the time factories all shut down. A GIF, of course, is an image format that allows for multiple images to be represented in sequence as the file references its own palette, producing (or reproducing) simple animations in repetitive, somewhat static loops. The GIF is the vaporwave artifact par excellence – especially now, in its long afterlife, where image and spring break forever come together as one in a strange and endless ballet under the red desert sun of the real.

As an example of vaporwave literature, J. G. Ballard’s collection of short stories Vermilion Sands (1971) is incomparable. It is also a literary GIF; the entirety of the book could be reconstructed out of wordless GIFs with no aesthetic loss whatsoever. But it is not fundamentally a hybrid object, like Jon Bois’ melancholy, mutating hypertext 17776: What Football Will Look Like in the Future (2017: “To pass all that time, many Americans have turned to football, contorting it in a variety of strange ways to suit their new reality”). Unlike Dennis Cooper’s GIF “novel” Zac’s Haunted House (2015: “an experience somewhere between carnival mirror labyrinth, deleted Disney snuff film, and a deep web comic strip by Satan”), which Cooper first created as a specifically visual artifact intended to emphasize intersections, juxtapositions, and loops, Ballard’s stories are resolutely textual.

Or are they?

After all, each story targets a specific media form: sculpture (“The Cloud-Sculptors of Coral D” and “The Singing Statues”), opera and horticulture (“Prima Belladonna”), painting, poetry (“Studio 5, The Stars”), fashion (“Say Goodbye to the Wind”). Each one reflects – no, refracts – how media become entangled in, or perhaps even constitutes, the strange loops of desire and dream that unfolds within and beyond the prison of the human psyche, opening it up and splaying out the psychological strata of all our looping, nested dreamworlds. Recall the horrifying, and horrifyingly suggestive, nature of the libidinal “body,” or landscape of desire, as autopsied by Jean-François Lyotard in his Libidinal Economy (1974): “All these zones are joined end to end in a band which has no back to it, a Moebius band which interests us not because it is closed, but because it is one-sided, a Moebian skin which, rather than being smooth, is on the contrary covered with roughness, corners, creases, cavities […]” Much like how the GIF is a “flat” image (even superflat), yet captures both depth and motion traversing the deeps. This is what it means to speak Muybridge, after all. You probably think Stephen Wilhite invented the GIF – and he did, in its current disguise – but it was Eadweard Muybridge who first uncovered the primordial form of the GIF, lurking in the world’s heart like a fossil from the future. Imagine a paleontology of the future, an idealistic morphology of media artifacts, waltzing backward through time, approaching the event horizon of the perpetual now, the long 2016… Vaporwave literatures invert media archaeologies.

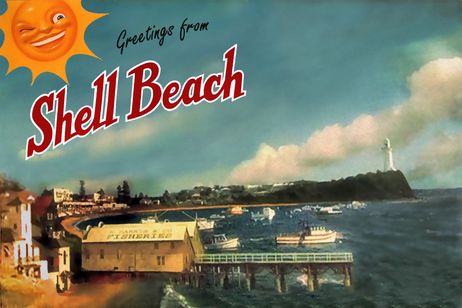

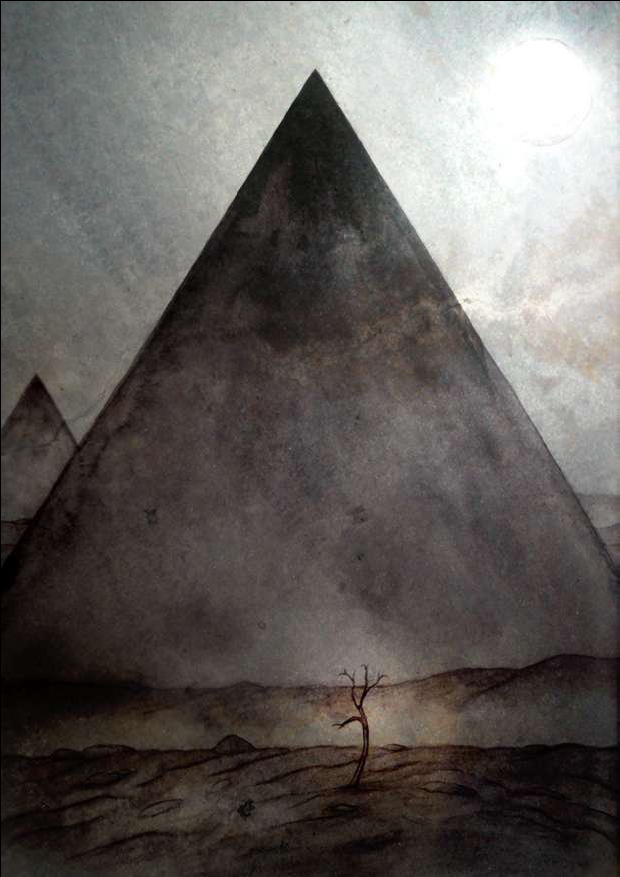

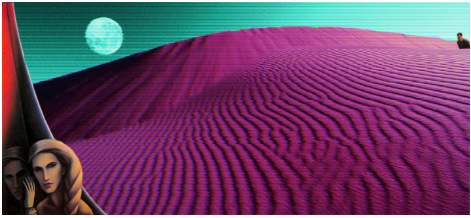

Back to Vermilion Sands: “No one ever comes to Vermilion Sands now, and I suppose there are few people who have ever heard of it.” So, what even is Vermilion Sands? It’s a “bizarre, sandbound resort with its lethargy, beach fatigue and shifting perspectives.” It’s a dream archipelago of abandoned villas, awash in crimson sands from the environing desert, shadowed by flying albino and purplish sand rays, “wheeling above the rock spires in the blood-red air.” It’s the posttraumatic landscape of the arts, all of which operate like so many ghostly robots, totally burned out but still fueled by vaporous promises. Vermilion Sands is a hologram: it looks a lot like things happened there, but remains peopled by dead souls and the dying stars, fragments of subjects from a Golden Age that never existed. Vermilion Sands is the primal scene of the end of history, casting neon shadows out of time.

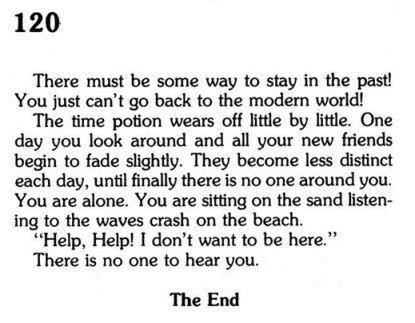

“The Thousand Dreams of Stellavista” (originally 1962): “All the houses in Vermilion Sands were psychotropic.” In other words, the architecture is perpetually plastic undeath, adapting to the drives, moods, and quirks of the occupants and always carrying the psychic impress of former occupants inside its mutable and rippling structuration. Imagine being haunted by abstract moods; imagine living inside an undersea fan, gently swaying. “Living in one was like living in someone else’s brain.” Howard Talbot and his new wife, Fay, buy a new house at 99 Stellavista. All the perennials are polyurethane. There’s a heart-shaped swimming pool in the foyer. Through its glass bottom, you can see the garage, the finned car parked below “like a coloured whale asleep on the ocean bed.” Its previous owner, Gloria Tremayne, had been a beautiful, diaphanous woman “with a powerful and oblique personality,” a movie star who murdered her husband to end his abuse. Ironically, Howard had been the assistant to Gloria’s lawyer at the trial, ten years ago. “The water was motionless, a transparent block of condensed time.” But the house remains haunted by Gloria’s psychic residues, which enfold Howard like a mass of invisible tentacles; the house grows jealous of Fay and tries to murder her, too. Howard becomes increasingly entranced, all wrapped up in the fossilized contours of this doomed movie star’s emotional echoes. The house, “like an anguished squid,” flexes and changes color. “The place must have been insane. If you ask me it needs a psychiatrist to straighten it out.” But Howard can’t break the spell of its psychoactive past; the house beckons him into its plasticine embrace. Fay’s long gone. You could give everything to the past which ensorcels you. But for now, at least, the house is turned off, and yet I know that I shall have to switch the house on again” (this always happens in Ballard)

“The Screen Game” (originally 1963): “Soon we were overrunning what appeared to be the edge of an immense chessboard of black and white marble squares. More statues appeared, some buried to their heads, others toppled from their plinths by the drifting dunes […] the whole landscape was compounded of illusion, the hulks of fabulous dreams drifting across it like derelict galleons.” Paul Golding, an artist, returns to the scene of the failed Orpheus Productions flick, Aphrodite 80. Like many of the artists who encounter (or haunt) the desolate, lush fastness of Vermilion Sands, Paul had been experiencing a “creative pause” (in his case, “showing signs of beach fatigue”). Specifically, Paul has been employed to paint numerous screens that would serve as the backdrop to the obscure psychodrama of this film, staged as a comeback for the dishy, mentally unwell actress Emerelda Garland, a ghostly Venus… “Decorated with abstract symbols, these would serve as backdrops to the action, and form a fragmentary labyrinth winding in and out of the hills and dunes.” Paul meets Emerelda multiple times; she is attended by jeweled insects who seem to be expressions of her underlying psychic state, or at least somehow under her control: “I felt that I had strayed across the margins of a dream, on to an internal landscape of the psyche projected upon the sun-filled terraces around me.” The director, Charles Van Stratten, reveals to Paul the purpose of the film’s production: “Its sole purpose is therapeutic […] I’m convinced the camera crews and sets will help to carry her back to the past […] It’s the only way left, a sort of total psychodrama […] With luck, the screens will lead her out into the rest of this synthetic landscape. After all, if she knows that everything around her is unreal she’ll cease to fear it.” Note that Ballard writes “The Screen Game” two years before John Fowles published The Magus (and both get echoed in The Prisoner). The grand psychoanalytic ritual (or is it a trap?) goes awry, of course: Charles Van Stratten, a petty tyrant, is swarmed to death by Emerelda’s “armada of jeweled insects.” The production ends, and only years later does Paul return to the deserted villa, to the ruins of the backdrops he had painted. “The whole question of the illusions which exist in any relationship to make it workable, and of the barriers we willingly accept to hide ourselves from each other: How much reality can we stand?”

“Cry Hope, Cry Fury!” (1967): “Hunting for rays, I sometimes found myself carried miles across the desert, beyond sight of the coastal reefs that presided like eroded deities over the hierarchies of sand and wind. I would drive on after a fleeing school of rays, firing the darts into the overheated air and losing myself in an abstract landscape composed of the flying rays, the undulating dunes, and the triangles of the sails. Out of these materials, the barest geometry of time and space, came the bizarre figures of Hope Cunard and her retinue, like illusions born of that sea of dreams.” Note: “I was twenty miles from the coast and my only supplies were a vacuum flask of iced Martini in the sail locker.” After crashing his yacht, Robert Melville is taken in by the mysterious Hope, recuperating under her care at the isolated Lizard Key: “both villa and island had sprung from some mineral fantasy of the desert.” Hope is a painter, and Robert becomes her model as he recovers. But these paintings are psychogenic, or perhaps even mutagenic… “Given a few hours each day, the photosensitive pigments would anneal themselves into the contours of a likeness […] Little did we realize what nightmare fish would swim to the surface of these mirrors.” The paintings, somehow, become haunted by another figure; in the background of this endless, hazy misadventure, a disconcerting figure stalks Lizard Key. Hope has a ghost, it seems. A former lover, supposedly murdered, but who survived the attempt. “I tried to explain why Hope had shot at him, this last attempt to break through the illusions multiplying around her and reach some kind of reality.” Libidinal fog embraces everything, heightening the hyperreality of these starkly blurry images, like a Gerhard Richter painting in drag.

You’re getting the vibes: a man, typically some kind of artist or functionary, ensorcelled by his own visionary encounter with a doomed icon of desire from the past, who exists as a real or virtual specter haunting some media form or another. The landscape is decadent, though not depraved; time no longer really exists in Vermilion Sands. Recurrent throughout the stories is the intimation of a “Recess,” “that world slump of boredom, lethargy and high summer which carried us all so blissfully through ten unforgettable years.” When the Recess ended, it “started up all the clocks and kept us busy working off the lost time […]” This is the endlessly looping fever dream of Vermilion Sands: imagine the red desert, crisscrossed by the fading yet perversely resilient libidinal intensities of a faintly posthuman class. Ivory rays glitter in the skies above you. You board the shining silver yacht that will take you into the deeper wastes. In the shifting sands, you will find mysterious artifacts, treasures of the past, strange remnants of a whole culture mummified by the omnipresent heat. Here, time is a painting of a stopped clock…

My edition came with 3D glasses included. But the glasses are cursed. Or perhaps they emancipate one’s vision. Wearing them, you see in Ballardian all the time now. All I know is I can’t take them off anymore. These mallwave mirrorshades have become adhered to the very structure of my face, like a Cronenbergian artifact. I think its fused with the bones of my skull. I can feel them restructuring my psyche, penetrating the distant recesses of my desire, reworking the primordial sludge of self into strange new chromium sculptures. Even if I could, I’d no longer remove them.