Vaporwave Megatext:

code beast by simon sellars

Written By: Michael Uhall

Published On: September 25th, 2023

Can there even be such a thing as vaporwave literature?

If so, what could such literature do, which isn’t already done, or done better, by other literary forms and modes of expression? For example: cyberpunk, post-cyberpunk, the New Weird, anonymous and distributed literary projects like _9MOTHER9HORSE9EYES9, the “open pop star” Luther Blissett, the pseudonymous collective Wu Ming, the theory-fictions of the CCRU or 0(rphan)d(rift>), and so on? Smash cut from Neuromancer’s “Hong Kong on a really bad day,” its sky “the color of television, tuned to a dead channel,” to Lavie Tidhar’s Central Station: “The smell of rain caught them unprepared. It was spring, there was that smell of jasmine and it mixed with the hum of electric buses, and there were solar gliders in the sky, like flocks of birds. Ameliah Ko was doing a Kwasa-Kwasa remix of a Susan Wong cover of ‘Do You Wanna Dance.’ It had begun to rain in silver sheets, almost silently; the rain swallowed the sounds of gunshots and it drenched the burning buggy down the street […]” There are exit ramps along this literary superhighway – to George Alec Effinger’s Budayeen, to Ian McDonald’s Brasyl, even to China Miéville’s New Crobuzon.

So, what could vaporwave literature even do, which could be said to exceed or surpass all these grimy, neon-drenched speculative cities and locales, these psychogeographies of the future, littered with artifactual echoes, stalked by ambivalent pin-ups decked out in chrome, all the fantasmatic junk of a virtual culture haunting its own labyrinth? Imagine meeting the ghost of yourself; imagine a literature that functions like a darkly mirrored multiverse. Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear. There’s our answer, lurking like a fractal dolphin somewhere down inside the semiotic spiral.

If there is vaporwave literature, it is hologrammatic. A hologram is an image, of course, a projection of a three-dimensional object made of light, which appears as such, but nevertheless doesn’t exist in three dimensions at all. Holograms are illusions. Each part encodes, or refracts, the whole image. From the little shiny pictures on your identification papers to complex, moving ghosts (like Tupac Shakur’s temporary resurrection in 2012) or digitally spawned reflections who never were (like Hatsune Miku), temporally distended symbolic performances (of body, depth, and motion) no longer require personal identity. Identity itself becomes structurally analogous to the commodity form. I am become fungible, destroyer of dreamworlds…

If there is vaporwave literature, it is hyperreal. This does not mean it depicts anything caricatural, exactly, as much as, instead, it mobilizes the avatars and gradients of meaning already latent in the world around us. Waking up all the twitching spirits of a consumer culture that only delivers marketing materials for itself, the ultimate cargo cult, dedicated to spam, stranded on the terminal beach at time’s end. Vaporwave literature mobilizes and unveils these spirits in ways that flense away the material lag factors obscuring the virtual plaza and all its technicolor glory, the dead mall where we’ve been stuck together for a long time, listening for the zombies outside… Look around you: “Look at you, hacker: a pathetic creature of meat and bone, panting and sweating as you run through my corridors. How can you challenge a perfect, immortal machine?” Look around you: everything glows and pulses, helplessly and hopelessly alive. Or is it? Imagine peeling back the skin on your hand, like plastic wrap off chromium bones. Were you ever really here? You’ll know nothing, and be happy…

If there is vaporwave literature, it is an endless fever dream, an alien blipvertbeamed directly into the meat of your brain and animating the shell of you, filling you up with fantasies, nightmares, and promises. Bisexual lighting in prose at the end of history. Libidinal vaporware. Vaporwave literature is the literature of the eternal present, trapped in diffuse, neon amber, lurking just out of reach. You can never touch a hologram, after all, and having a fetish for ghosts will get you nowhere fast. In a formula (like a brand catchphrase, repeated by pixelized parrots, glowing bright, and self-extracting directly into the archive of your dreams): Vaporwave literature is the hologrammatic, hyperreal literature of the eternal present. Like Philip K. Dick’s Counter-Clock World (1967), causality works differently inside the vaporwave megatext. To produce the illusion of forward momentum, it ties itself in knots, all tangled up in prosodic shibari. The prose becomes turbid, turgid, turnt. You still think you live in time, but the time factories have all stopped production. You live in the model house of history, just outside the city limits of Marienbad; out of canned goods, your culture is eating its own echoes. Welcome to the enormous space…

As a first example, take Simon Sellars’ Code Beast (2023). In many ways, as we will see, it is paradigmatic of vaporwave literature, this marginal literary animal, or ghost of such an animal. What’s Code Beast about? The text summarizes itself: it’s about “watching the man that I was enter the code beast that I am” (49). But what does that mean?

The Setting:

Code Beast takes place in the near future. In it, the Vexworld supervenes base reality, called the shell world, a crapsack world existing as an afterthought, a cybernetically-infected, post-apocalyptic hell world: “The shell world is dying, and no one knows first aid. Extreme virtuality is the repudiation of that uncertainty” (121). Everything is saturated with augmented realities and artificial intelligence, living hardware, nanotech bots, and predatory architectures. It’s the metaverse gone wild. And everything is glitching out. Or is it? Who would even want to live in the real world, after all? It exists at the lowest level. Virtually in the sewers. Stalked by who knows what, armed with shining knives. Your reality’s a fucking drag, man… People trapped forever in the shell world are called two-percenters: “part of an underclass that can never be released. They’re locked out of the Vexworld for whatever reason, bad credit or bad eyes, and they’re insanely envious of those that aren’t. Well, who wouldn’t be? They’ve been sentenced to slow death […]” (91). The Vexworld, by contrast, is a nightmarish fractal of complex permissions, digital animals, hybrid intelligence, legacy code, whole spiral galaxies of mutually incomprehensible bubbles of solipsism or tribalism, only partly legible to non-subscribers (“producing recombinant animal species inside an infinite ecology” [17]). You constantly manipulate conceptual and sensory navigations using cheaters, implants in your eyes that transport you, eyes rolling back and whiting out. (“Cheaters were originally developed to restore sight to the blind, using a combination of bulky cameras embedded in the skull, memory prosthetics, and primitive VR. It was the beginning of the Vexworld. When that application proved overwhelmingly successful, the technology was adapted into mixed reality for sighted people and the Vexworld grew into an interdimensional maze” [176].) Remember, the eye is the only part of the brain that can be seen directly. It begins when the machine starts riding you when you become a donkey for an abstract machinic intelligence that uses bodies for bootstraps. “Acceleration breeds mutation” (16). Imagine taking the singularity seriously, but building it in the world you’ve got, instead of some glittering solarpunk reverie. Imagine an infinite stack of Second Lives, painted over everything, layered to the nth dimension. Ever seen a window painted shut? Now, imagine that window is your eyes. You’d be surprised by what goes bump in the net.

The Plot:

Kalsari Jones (“I’m tired of being second banana in this non-stop clown show” [172]) is suffering the cronk: “a by-product of sustained, fully immersive vexing. When you’re deep inside the Vexworld, your body forgets that it has a physical correlate. The capillaries on the skin are perpetually raised to compensate for the disembodied sensation, forming unencapsulated mechanoreceptors on the epidermal topography” (28). “Where is my actual body? […] I have lost the texture of it. All I have is the light-born persy that I now inhabit, and I must trust that I have a physicality somewhere. I was going to say ‘up there’ but there is no up or down where we are” (101). Kalsari Jones is fighting with Rimy, the genderless love of his life, an artificial intelligence he created to be his companion. He likes to fuck code, but they’ve gone and dumped him. He’s devastated, picking fights with every AI he meets in the surrealist ARG of life in a post-truth world. So, Kalsari Jones is going to rehab. Sanderson, Jones’ “chronosthesia supervisor,” insists: “I’ve let you operate like a bucking bronco for too long, but no more. Now, let me tell you exactly how it’s going down. You will submit to Ingram, and he will cure you of your digisexuality and your rampant vexing. He will break you down and reintroduce you to normality. You will be whole again, no longer a creature of fragmentation” (164). That’s the deal; that’s the imperative. Go to the Magic Mountain, and find yourself there. If only you knew. So, Kalsari Jones goes to meet Ingram Ravenscroft (a “shadowy physician grown monstrous in my mind” [171]), looking for the cure to being himself. And Ravenscroft (part Dr. Adder, part Dr. Benway, possibly named after the anthroposophist Trevor Ravenscroft) delivers. This guy’s into some weird shit: “We’ve been conducting focused training sessions, developing protocols for something called remote viewing” (250). Re-imagine Project Stargate as a kind of nominally psychotherapeutic cult intended to bootstrap… well, something. Jones: “I don’t get it. […] In the shell world, everything has been mapped and every object is wired. There are trillions of grain cams floating through the air, no blind spots left. We can travel to mirror clones and experience those coordinates exactly as they exist in the shell world, or we can savour them from a distance. Isn’t that the very definition of remote viewing? That’s why it’s ludicrous to talk about adepts and psychic powers. We’re all psychic now […]” (256). Turns out, Ravenscroft is trying to break down and rebuild his disciples into a new kind of First Earth Battalion, into combat parapsychologists custom-made for the Vexworld: “We hunt ghosts. Digital ghosts. We call them glitchglots. They’re an evolution of spamglots, a virulent new species, more resilient than previous variants. They’re sentient, with the ability to infect targeted cheaters […]” (227). Strangely, this dovetails with one of Jones’ fixations: “How many digital ghosts would pass through my body at any one time? Now I know I can never be rid of them because the signals have infected me, turned me inside out, made me a grotesque mimicry of what I once was” (24). Think of this in terms of Wi-Fi; think of this in terms of all the invisible code strings and encrypted messages (texts, wire transfers of vast amounts of money, sexts of unimaginable depravity) and gaming sessions passing through your physical body right now. You can’t see any of it, without the right devices, and sufficient access, but it’s all there, right now, swarming around you, like spermatozoa, seeking entry… They want to make something new of you – and they have. In the end, it seems, everything shifts yet again. Jones, himself, has always been a digital ghost, the code beast he therefore is: “More than human. Less than an animal” (262). In other words: Jones has never been a real boy. He is an echo of someone dead, a digitally resurrected deepfake, a grief tech artifact suffering the (data)bends. “‘Have you heard of hyperstition?’ Halo says. ‘Hyper what?’ ‘It’s a theory of creative energy. According to believers, by participating in ritual acts of fantasy, the fantasy can be made real. The scenario is actualized through a combination of pure thought and ritual repetition” (303). In 2022, the MIT Technology Review asks, “Technology that lets us ‘speak’ to our dead relatives has arrived. Are we ready?” From the Vexworld future, Dr. Ingram Ravenscroft writes a reply: the paper’s title “Sentient Glitchglot Cheater Infection: From Discovery to Ongoing Review” (n.d., 327-349). One recalls something Marshall McLuhan writes to Eric Voegelin in 1953: “a person feels like an awful sucker to have spent 20 years of study on an art which turns out to be somebody else’s ritual.”

The Conclusion

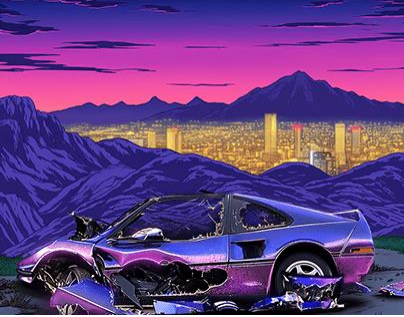

So, the Code Beast eats itself. Echoing Virilio, “The flipside to any new technology is the accident. Invent the car and you also invent the car crash” (91). Transplant this science-fictional fever dream into the vaporwave megatext. Crash them together. We started with the following question: What can vaporwave literature do? Sellars gives an answer. He takes us on a submarine trip into the gritty tain of a darkling mirror. Ocean grunge in prose. What cryptids, what squid live here? Underneath the glossy, rippling, aquamarine-and-pink surface of the perceptual stack of experiences and spam filters and subscription plans, what remains? Can you dig down that deep, through the strata of perceptions? Can you find the bones of the earth? Consider: To vex (verb): from the Old French vexer, “to harass,” from the Latin vexare, “to shake, jolt, or toss violently about, to attack, harass, trouble, or annoy,” from the PIE root *wegh-, “to go, to move, to transport.” Invent the car, and, congratulations, you’ve also invented the car crash. But, as J. G. Ballard teaches us (and who knows this better than Simon Sellars?), crashes are really just opportunities in disguise.

Kalsari Jones, the posthuman Möbius strip, is a ghost, a ghost with a fetish for being real. He is, we are, code beasts just like all the others. And Code Beast reveals something about the kind of subject who haunts the virtual plaza. Broken, impossibly smooth marble statuary. The sensory theater flickers as the power stations of the previous world slowly die. When you look away, the subject gets closer – until you merge together, becoming one new thing. Avatars of a weird past that never existed, heralds of a future that will never arrive (which is always arriving). Sellars shows us that the dreamworld of the posthistoire, the virtual plaza, is populated with the living dead, with undead icons going through strange loops of spasmodic behavior, like twitching holograms on repeat. We have vaporgrave personalities; identity is millenarian vaporware… Time for the Virtual Exodus™…

Coming up next on the playlist (it’s on shuffle and repeat): Philip K. Dick’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1964), J. G. Ballard’s Vermilion Sands (1971) and Kingdom Come (2003), Bret Easton Ellis’s Glamorama (1998), William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition (2003), Tom McCarthy’s Satin Island (2015), Dempow Torishima Sisyphean (2018), Scott R. Jones’ Stonefish (2020), David Roden’s Snuff Memories (2021).

If you would like to check out Code Beast. You can preview or buy a copy,

Here!