VAPORWAVE MEGATEXT:

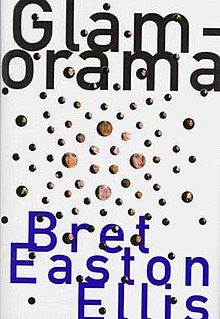

gLAMORAMA By bRET eASTON eLLIS

Written By: Michael Uhall

Published on: Sunday, November 10th, 2024

“If there is anything that this horrible tragedy can teach us, it’s that a male model’s life is a precious, precious commodity. Just because we have chiseled abs and stunning features, it doesn’t mean that we too can’t not die…” – Zoolander (2001)

Page one tells you everything you need to know about Victor, protagonist of Bret Easton Ellis’ underrated and underread 1999 novel Glamorama: “Who the fuck is Moi? […] I have no idea who this Moi is, baby.” Indeed, this is the question around which everything else in the novel turns: Who is Victor Ward? (This question could almost serve as the vaporwave inversion of the same question, in another context, about a certain John Galt…)

On the one hand, the answer to Victor’s question is straightforward. Ward is a male model, the current “It Boy,” and a stupefyingly vacuous denizen of celebrity and fashion culture. Despite his many aspirations (including scoring a role in the then-satirical idea of Flatliners 2, a movie no one needed or wanted in 1998, or one year after we passed through the event horizon of time itself, in 2017, when this movie, unironically, was actually made…), Victor is one hollow man among many.

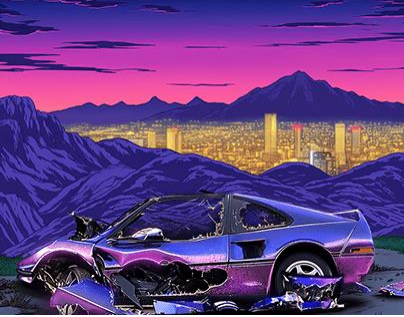

Art by @Cerulea_dlux

When the novel opens, he is trying to open his own small night club, virtually under the nose of his erstwhile boss, Damien, a nightclub owner and also the romantic partner of Alison Poole, with whom Victor is having a meaningless affair. He is a creature of pure appearances. Indeed, you could say his whole life is a meaningless affair – this is one of the recurrent objections raised by his girlfriend, top supermodel Chloe Byrnes: “You don’t care about things that don’t have anything to do with you” (158). “So you don’t have any lip balm?” Victor replies, entirely in earnest.

On the other hand, Victor Ward is also Victor Johnson, son of the ambitious Senator Johnson, who lowkey finds Victor a disappointment and an embarrassment:

“You’re not a loser, Victor,” Dad sighs back. ‘You just need to, er, find yourself.” He sighs again. “Find – I don’t know – a new you?” “‘A new you’?” I gasp. “Oh my god, Dad, you do a great job of making me feel useless.” “And opening this club tonight makes you feel what?” “Dad, I know, I know – ” “Victor, I just want – ” “/ just want to do something where it’s all mine,” I stress. “Where I’m not… replaceable.” “So do I.” Dad flinches. (79)

But by the end of Glamorama, Victor, in fact, has seemingly been replaced, whether by a Manchurian Candidate version of himself or by some postmodern literary surrogate. At this point, Victor Johnson and Victor Ward quite literally seem to split in two – and this is not a metaphor. Victor Johnson, who supplants the Victor we’ve been following all along, is getting his life together, moving on from whoever Victor Ward is now.

“Goodbye,” this new, improved Victor (or, rather, his replacement) tells Victor on the phone, in one of the novel’s late moments of surreality (476). Meanwhile, Victor Ward, imprisoned in a safehouse in Milan against his will, is trying to get his life back. He fails. Even former intimates, like his sister, fail to recognize him when he sneaks in a phone call. Indeed, his physical execution seems imminent. The lifespan of the husk is over. Ultimately, he is a disposable man, the citizen and then refugee of a disposable culture

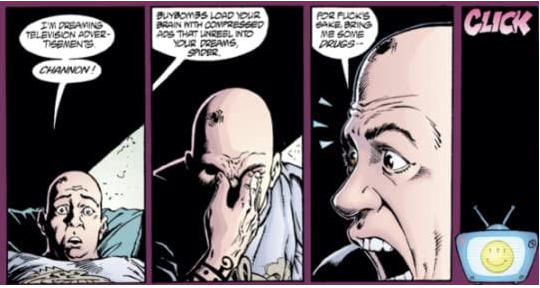

In one sense, Glamorama is about Victor’s inability to integrate the real into the play palace of his perceptions. His world exists in an almost purely semiotic register. Hence, the novel’s incredible fixation on listing brands and the names of celebrities, in vast chains of association and depthlessness. Who’s in; who’s out; who’s where; who’s not. Whether they’re even really present at the party is irrelevant. What matters are the invocations and lists themselves, the decorative citational explosions that guild the undead lily of a life lived entirely inside the virtual plaza. These explosions of hyperreal intensity leave behind detritus – like confetti scattered on the sticky floor the morning after a big party, or the dread and irritating “specks” (often interpreted by Victor as mysterious confetti) that continually intrude into the bisexually lit soap bubble of Victor’s sensorium. Welcome to the desert of the real, indeed; the sand gets in everything…

Art by @Uy_que_Paila

So, Victor cannot acknowledge or integrate the real, either because he is so structurally deformed and shallow, or perhaps because he is himself a kind of projection, a cheap hologram, a false self, an escape route posed by some other self. Imagine finding out you are nothing more than a cover story, your personality (or lack thereof) a mere pretext for some deeper, stranger politics, beamed into the virtual plaza from a VIP dimension or some cosmic plane you’ll never be allowed to enter. Indeed, throughout Glamorama, Victor constantly encounters people who mention seeing him in places he wasn’t, at fashion shows and openings he did not attend: in Miami, at the Alfaro show, at Pravda last week. (One recalls a brief scene from Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups [2015], which explores the same themes as Glamorama, but with a rather different trajectory to the narrative… Christian Bale’s character is being robbed, but the thieves are frustrated at the emptiness of his life. It’s an existential joke, or a riddle: What is a life that contains literally nothing even worth stealing?) This never fully, consciously registers for Victor, beyond occasionally irritating him, because he wishes he’d been there instead of his distant doppelganger. No further questions.

Likewise, Victor seems to believe increasingly that events in his life are scripted or staged. This does not alarm him. If anything, it’s a source of strange succor; events have the promise of meaning, perhaps, if they unfold in the sixteen-millimeter shrine. He perceives increasingly the ghostly presence of film crews, intimate conversations with mysterious directors, and other people in the flux of life around him, who appear as characters or “extras.” In part, Victor is incapable of understanding the events of the novel’s plot outside of this framework. Indeed, these events may be inaccessible, structurally occluded, haunting the text itself. After all, within the glamorama, everything is appearance (consider the etymology of “glamour”…). What better framing device, then – or refuge – than to perceive all the happenings of your life as if they’re just part of the movies, if these horrific and terrifying events represent some internal logic rather than the fatal trajectory of a car crash with the Outside?

Ultimately, Victor falls in with a group of nihilistic supermodels who have, for reasons Victor is never fully able to understand, started a vast campaign of stochastic terror and hideously random violence. Their leader, Bobby Hughes, is himself a former It Boy, a male supermodel of incredible charisma, since retired. Victor encounters Bobby’s gang almost (but not actually) inadvertently. After fucking things up in the States, Victor is recruited via skyhook to go to Europe in order to track down an ex-girlfriend, who supposedly has gone missing (she hasn’t). The man who recruits him does not exist. Again, Victor has few questions. Quelle chance!

But the sense of dread in the novel grows and grows. It’s like Victor can see disaster approaching, just out of the corner of his eye. But, since he’s always avoiding it, or in some way unable to register the real, he never focuses on what is happening in –or to-the world around him. As Bobby tells Victor, when Victor asks why Bobby seems to like and trust him: “Because you think the Gaza Strip is a particularly lascivious move an erotic dancer makes […] Because you think the PLO recorded the singles ‘Don’t Bring Me Down’ and ‘Evil Woman.’” Also, note how the chapters are always counting down. To what, or whom? Quis est iste qui uenit?

Precisely here Glamorama becomes comprehensible primarily as a vaporwave novel: Victor, denizen (and ultimately victim) of the virtual plaza, encounters the radical exteriority of a world that exceeds the hologrammatic dead mall dimension where his dreams play out. Perhaps, in the end, he’s the only person who ever really lived there. Consider again the etymology of glamour: “1715, glamer, Scottish, ‘magic, enchantment’ (especially in phrase to cast the glamour), a variant of Scottish gramarye ‘magic, enchantment, spell, said to be an alteration of English grammar (q.v.) in a specialized use of that word’s medieval sense of ‘any sort of scholarship, especially occult learning,’ the latter sense attested from c. 1500 in English but said to have been more common in Medieval Latin.”

A glamorama, then, is perhaps an updated term for an illusory space, like a fairy circle, or a virtual machine, running in the void…

Pick up your copy of Glamorama from Penguin Random House here